Lost Time

Reception for the artist

9.12(Fri.) 17:00 – 19:00

Wako Works of Art is pleased to present the world premiere of Lost Time, a new installation by Dutch artist Fiona Tan, opening on 12 September 2025.

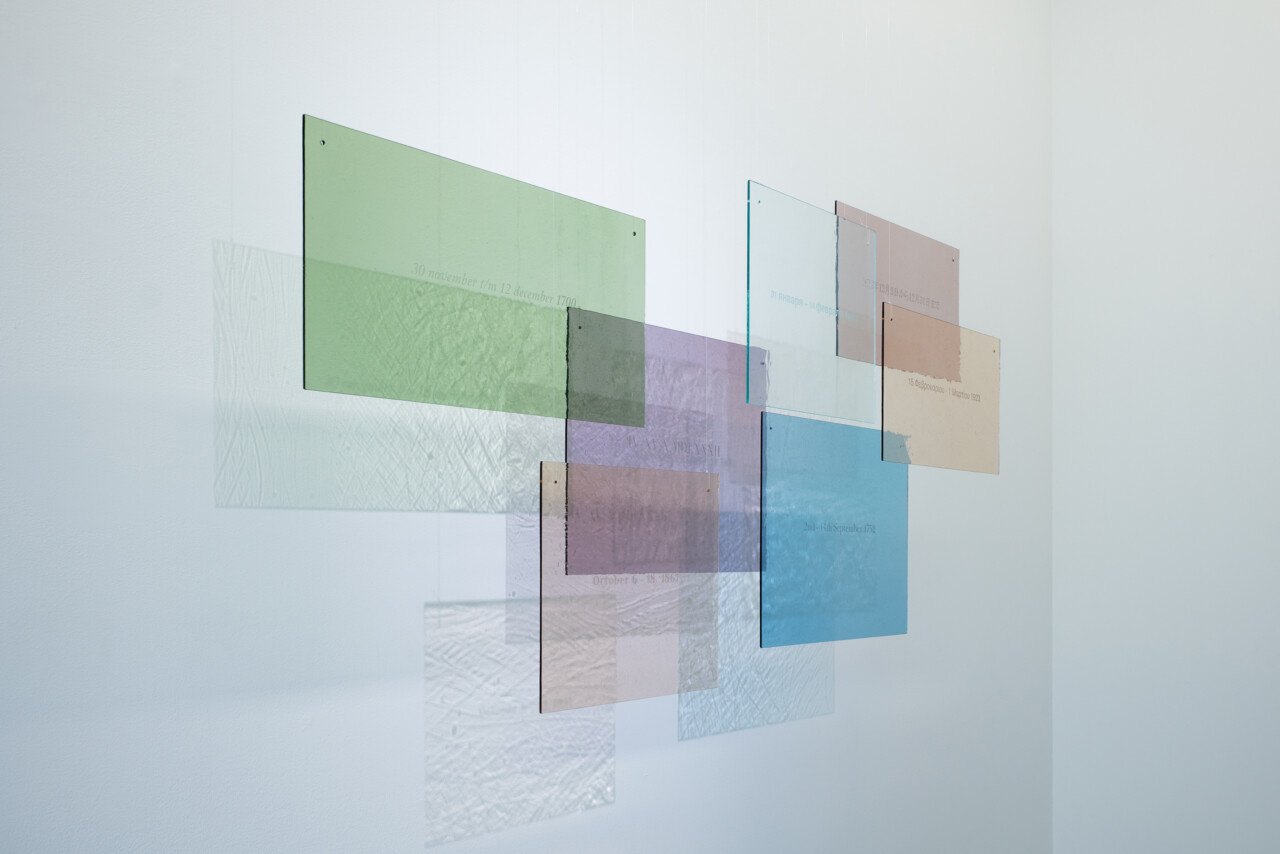

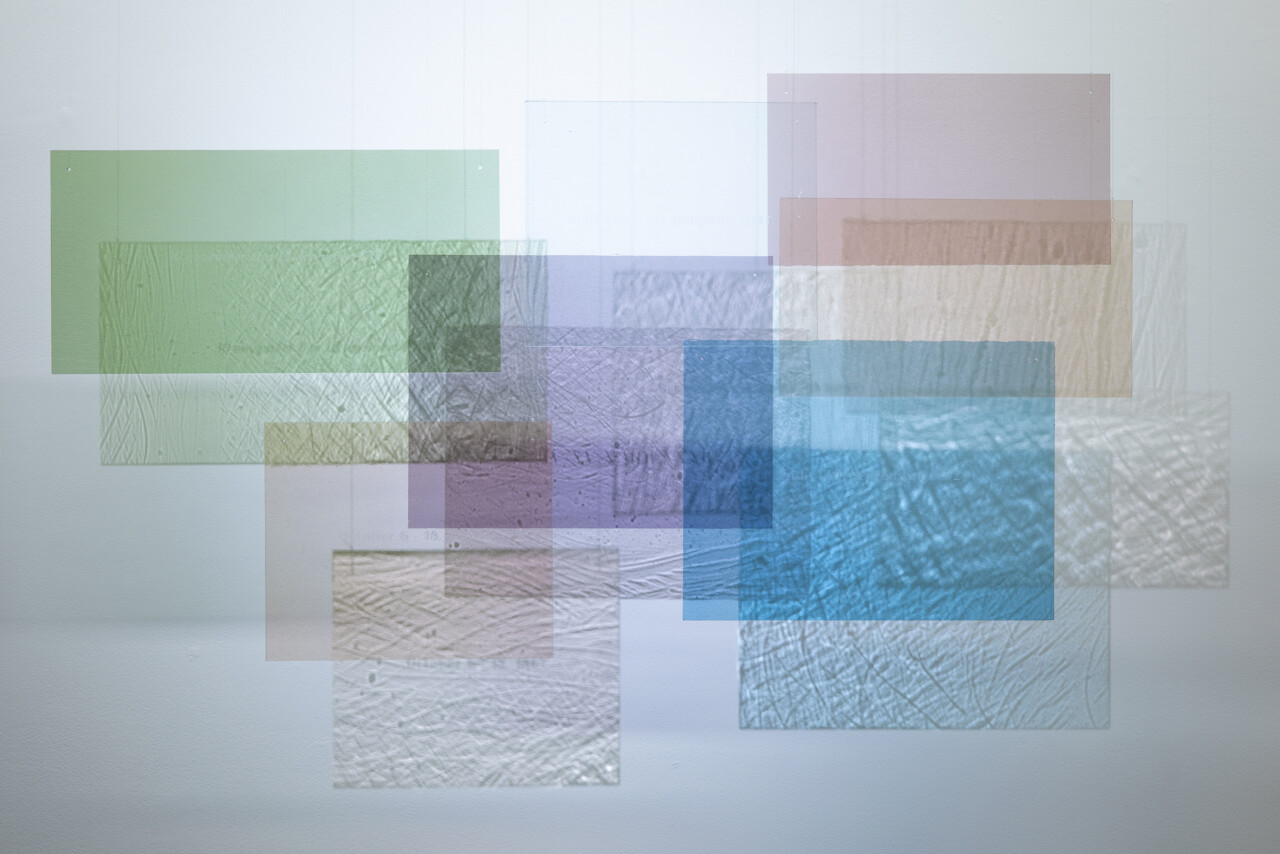

Lost Time is an installation of seven glass panels suspended from the ceiling. On each panel, the dates of various locations—Rome, Amsterdam, London, Alaska, Tokyo, Moscow, Athens—are sandblasted, the time interval that was removed from the calendar there when was reformed.

Since its introduction by Julius Caesar, the Julian calendar was widely used in the West. Because it reckoned the year as 365.25 days—slightly longer than the Earth’s actual orbital period—it drifted by roughly three days every four centuries. Over several centuries this error became impossible to ignore, increasingly disrupting the timing of annual events and religious festivals.

In response, astronomers and mathematicians refined the calculations, and a new calendar closer to the solar year was promulgated in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII. Amid debate, adoption spread between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries. Whenever a region switched calendars, a block of dates disappeared from its civil record.

Japan likewise changed its calendar in 1872, moving from the traditional lunisolar system (the “old calendar”) to the solar Gregorian calendar. Nearly one month vanished: the day after 2 December became 1 January of the following year, causing considerable confusion. Writers and intellectuals such as Fukuzawa Yukichi strongly advocated for the new calendar, helping it to take hold.

Lost Time visualizes these gaps created around the world. Slight offsets and overlaps among the glass panels produce a subtle visual tremor, inviting reflection on the depth of these historical absences.

Tan writes: ‘However perhaps even more strangely, some disgruntled citizens believed they had been robbed of time. They were convinced that the reform meant that they would die sooner than would otherwise have been the case. As the poet Philip Larkin says, days are where we live.’

Reactions to calendar reform reveal that when trust is shaken in everyday markers—paydays, anniversaries, birthdays, periods of mourning, beyond the merely numerical, time becomes a unit of feeling.